The motivation to write this week is that I’ve seen too many novice presenters who have been turned off from presenting because of negative and/or unhelpful feedback they have received in the past. Rushing to the defence of the critic, it’s only human nature to yell “speak louder” or “I can’t hear you”. However, presenting is not just about projecting. For example, if you forcefully project you may damage your throat and your audience may feel like you’re yelling at them. This is only one example of the quality of feedback we receive when we present. Presenting ‘you’, is about becoming aware of your own presentation style, the habits that define it, and making conscious choices as to whether or not you want to keep or change those habits when they are noticed by others.

The ‘Broken’ Coach

But at least most presenters don’t have to endure European physical theatre traditions. Long ago, I remember signing up for a course where the teacher practiced the fine art of cruel feedback….a common abusive technique in some physical theatre schools meant to disturb regular patterns of behavior. The belief was that in breaking up patterns, a truer ‘you’ might emerge and then the teacher could build you up with more ‘true’ impulses and responses. This is common to many performance traditions. The day I left, was the umpteenth time I came out on stage to present and before I could even mutter a word, the teacher once again just yelled “No. Again.” No explanation. No feedback, just negative reinforcement each and every time. There’s only so much unhelpful feedback that a person can take and when it comes to presenting the key motivation to coach someone should be to nurture them, not to simply highlight what they might be doing wrong. This only confuses the mind and creates uncertainty and chaos within it. While this may be part of the reason why that particular teacher I had provided feedback in the way that they did, especially in the domain of the clown, I have seldom seen it have any lasting benefit. More precisely, I have met more broken performers with their own horror stories than I have actual performers.

Now in the land of professional presentation, unfortunately, I’ve seen a similar pattern of unhelpful and/or unexplained feedback emerge. While many individuals assume they are coaching others because they have learned a particular way of presenting that worked for them at the time and that they continue to do, there is not usually a sensitivity towards:

- the context of a presentation which informs presentation style;

- what a person is already bringing to the presentation nor to the specific habits that they rely on to maintain audience attention;

- the vulnerable self that has already taken a risk being out there in front of others and doesn’t need another critically negative voice besides their own.

The result of negative coaching

For whatever the reason, the majority of individuals I have worked with are uncomfortable taking center stage. I don’t have quanitifiable numbers on this but I would say on average 70-75%. Most would resist the opportunity if they could. Although the motivation may at first be “because I have to”, or “only if I have to”, at least the experience can be made more nurturing so that they may actually whisper to themselves afterwards, “that wasn’t so bad”. This may make them more comfortable the next time. It means that there may in fact be a next time. Now for the minority of us who may well say “whatever…I can take the harshest of feedback cause I’m a lion..bring it.”—we usually settle in on a style that may not necessarily captivate an audience. Being comfortable presenting doesn’t always mean you’re a good presenter. That’s because we, like those less apt or confident to take centre stage, have mainly heard the following exclamations from a well meaning (I assume) coach: “talk louder, don’t mumble, don’t turn your back to us, stop fidgeting, be clear and concise, talk slower, etc…”. “Oh, so if I articulate, speak loudly, remain absolutely still and talk slowly, I’ll be a compelling speaker?”

In reality, the predominant response to these kinds of exclamations that I have witnessed over the years, is some form resistance. Why? In part, because in that moment of vulnerability it’s hard to take it all in. It’s hard to hear outside critical feedback when you’re too busy listening to your own judges. Also, because when we are asked to take centre stage and we are not loved for it, then the situation will make us feel bad and so rather than take the advice and shift, most people I’ve seen, will prefer not to go up and present again. Moreso, in most presentation feedback there is not enough time taken to convey specific information that recognizes what a person is actually doing, why they may be doing it at the time and the effect that it has on the audience. In other words, providing presenters with grounded feedback.

Solutions for both presenter and coach

One solution is a not-so-secret method used in theatre for hundreds of years to support an actor’s ability to more deeply embody performance practices that can communicate a story, message, pitch or idea, while maintaining an audience’s attention.

For the presenter:

- The first step is identifying all those voices that play in your head when you present. By making them visible through reflection you become more aware of their influence on your presentation. Along with these come the war stories. It’s good to acknowledge how they have influenced the way in which you present.

2. The second step is to go up in front of others and try new things out in a supportive environment. The only aspect of ‘you’ that needs re-building is confidence—that kind of confidence that is built upon the strengths that an individual already possesses. The kind of confidence achieved through trial, error, success and repeat.

Now the secret of supporting the novice or more experienced presenter’s attempts lies in the role of the coach—that important outside observer. This is where a coach’s experience presenting and teaching others does come into play. This is also where we see countless methodologies, approaches, steps, how to’s and rules of play emerge and sometimes, become trademarked. The coach needs to be discerning and needs to work with the individual in front of them.

For the coach:

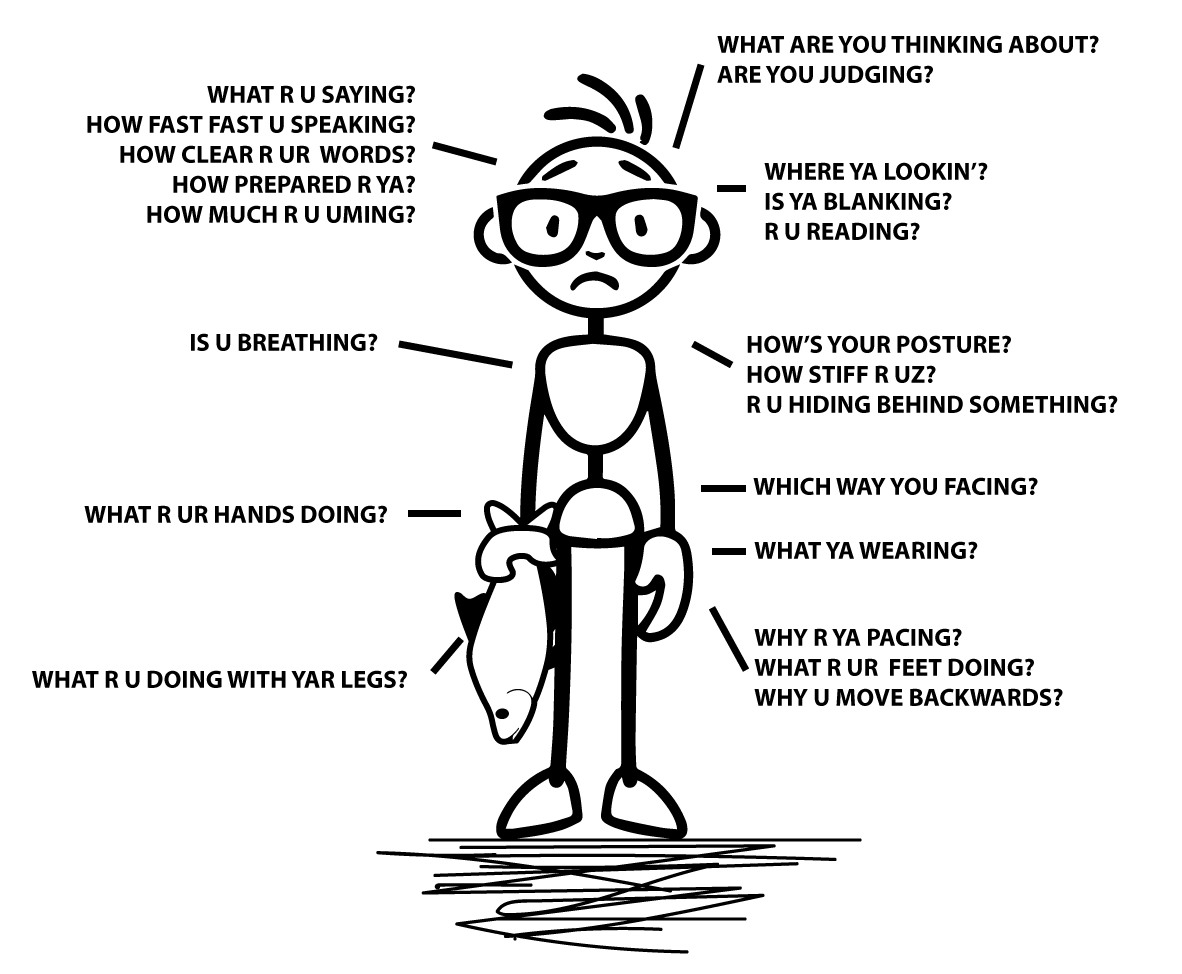

- Mirror back what the presenter does. In this way you work with what the presenter is bringing to the table. You are not communicating bias. There is no “you should” in the feedback. There can only be “Are you aware that you were doing ________? If you do ________, then the result ‘may’ be this”. If you have an audience, then you can involve them by asking what they feel when the presenter does _______________. The map below is for discerning coaches who may notice something a presenter is doing that may be preventing them from engaging an audience fully. These habits can become more clear by asking questions.

Speaker-Persona Character Drawing by Shabnam Suresh

Speaker-Persona Character Drawing by Shabnam Suresh

2. As coach, the next step is to ask the presenter to repeat what they presented and suggest a different approach. In this way you also see if they are ready to take direction. Not everyone is comfortable trying new things on the spot.

Every unarticulated word, every look away, every unconscious movement has meaning. Now it’s up to the presenter, if they wish to change what they are doing. In this softer approach, you are providing feedback and not telling how to present. You are simply providing options that a person can choose to use or not use.

Closure

What this blog can’t represent is the subtlety of working one-on-one with presenters in the moment. The demands and feedback are contextual and not all feedback works with all people. That said, in proposing a more nurturing relationship that can be easily developed between presenter and coach, based on my experience, we are likely to create more successful presenters—those presenters where the practiced habit of self-awareness and reflection become part of their own learning process in order to captivate audiences whenever and where ever they are asked to speak.

Leave a Reply